Painfully Funny: The Complete Directorial Works of Elaine May

35mm screenings

ICA London, September 2018

Ask any of the top American comedians of the past forty years to name their influences, and the name Elaine May is sure to come up. Alongside Mike Nichols she established a new kind of erudite, neurotic, satirical sketch comedy in the late 1950s, blazing a trail for a whole generation of performers to come. According to Lily Tomlin, “There was nothing like Elaine May. Her voice. Her timing. Her attitude.”

Steve Martin has admitted he used to go to sleep listening to the Nichols-May albums on repeat. Woody Allen, Martin Short, Judd Apatow and Tina Fey are among the legions of comics who have paid tribute to May, so why isn’t her work more widely available and celebrated?

The films of Elaine May should be regarded as key entries in the New Hollywood movement that emerged in the 1970s, but while the ‘movie brat’ generation of that era is still lionised, May’s films have slipped out of the conversation, and out of circulation. Watching her films today it’s clear that she was as adventurous and groundbreaking as any of her contemporaries. She subverted the romantic comedy with A New Leaf (1971) and The Heartbreak Kid (1972), and then she tested the bonds of friendship under extreme duress in Mikey & Nicky (1976) and Ishtar (1987). The latter film never recovered from its toxic pre-publicity, and became a notorious big-budget flop. Thirty years on, it remains the last film she has directed.

May has continued to write and perform in the subsequent decades. She received Oscar nominations for writing Heaven Can Wait (1978) and Primary Colors (1998), as well as doing uncredited work on films as diverse Reds (1981), Tootsie (1982), Labyrinth (1987) and Dangerous Minds (1995), but it is as a director that we can see the full flowering of her talents. She is a maverick artist who was uncompromising in pursuit of her unique vision, and the manner in which she has been neglected by Hollywood is shameful. “Her four films as a director are high points in American moviemaking,” Martin Scorsese has said, and we were proud to present this small but extraordinary body of work at the ICA on rarely screened 35mm prints, giving a whole new audience the opportunity to discover and celebrate a great American director.

You can view a pdf of the programme booklet for this season here.

A New Leaf (1971) – ICA, Fri 21 September, 6.30pm – Buy tickets here

Elaine May starred in her directorial debut as the timid and socially inept heiress Henrietta Lowell. “She has to be vacuumed every time she eats!” Henry Graham (Walter Matthau) exclaims in disbelief, but she is the perfect target for this bankrupt ex-playboy, who has designs on marrying and murdering a rich woman to reclaim his status among the elite. A New Leaf set the tone for May’s filmmaking career in a number of ways. It established the keen interest in relationships and betrayal that would remain integral to all of her films, and it brought her into conflict with the studio, which took the film away from her and drastically re-cut it. May’s original three-hour version, which reportedly contained two murders, is unlikely to ever see the light of day, but the film we have is a near-perfect black comedy, a stinging commentary on class, and a surprisingly affecting love story.

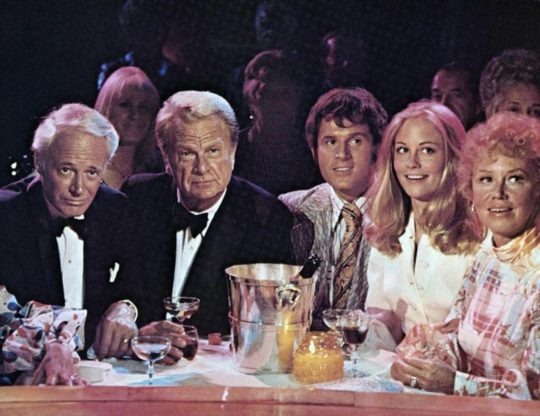

The Heartbreak Kid (1972) – ICA, Sat 22 September, 6.30pm – Buy tickets here

Written by Neil Simon, based on a short story by Bruce Jay Friedman, The Heartbreak Kid is one of the great American romantic comedies. The story of a man (Charles Grodin) who falls in love with a woman (Cybill Shepherd) he meets while honeymooning in Florida with his new bride (Elaine May’s daughter, Jeannie Berlin), the set-up is pure screwball, but May executes it as a brilliantly excoriating black comedy. Like Albert Brooks’ Modern Romance, it takes the tropes of the traditional romantic comedy and dismantles them one-by-one, twisting Thomas Jefferson’s American ideal of the pursuit of happiness into the selfish folly of a stupid, egotistical man. It’s a sharp, hilarious picture, which not only demonstrates May’s deft grasp of tone, but the remarkable breadth of her vision, as she betrays the influence of everything from classical Hollywood comedies to The Great Gatsby.

Mikey & Nicky (1976) – ICA, Sun 23 September, 4.00pm – Buy tickets here

Mikey & Nicky is Elaine May’s darkest film, and her most pitiless examination of masculine behaviour. Peter Falk and John Cassavetes play the small-time gangsters on the run from the mob, whose lifetime of memories and resentments come to the fore during one long, panic-stricken night. Developed through a long process of improvisation, with May often running three cameras simultaneously to capture every gesture, Mikey & Nicky transcends standard genre tropes and confounds audience expectations with its exhilarating, freewheeling style and the riveting intensity of the performances. Having been delivered months later than scheduled and wildly over budget, the film almost ended May’s filmmaking career, but it stands as arguably her most audacious and complex work, with the anticipated laughs gradually being stripped away to reveal the tragedy of a friendship that has been irrevocably broken.

Ishtar (1987) – ICA, Sun 23 September, 6.30pm – Buy tickets here

Ishtar, Elaine May’s latest, and certainly most underrated and misunderstood film, is the story of two musicians, played by Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, who become unwitting pawns in a diplomatic crisis after agreeing to play a concert in Morocco. The film flopped on release, but its ongoing notoriety speaks more to a sexist industry’s discomfort with a maverick female auteur than it does to the film’s quality. “If all of the people who hate Ishtar had seen it, I would be a rich woman today,” May quipped to Mike Nichols during a post-screening Q&A in 2006, encapsulating the absurdity of the film’s reputation. Ishtar marks the culmination of May’s morbid interest in unchecked male egotism, as her gaze shifts from the pathetic vanities and neuroses of her protagonists to those of the establishment itself. It’s a terrific takedown of Reaganite foreign policy, sharp and incisive, but full of the kind of raucous silliness modern viewers will recognise in the films of Adam McKay (“I can’t believe these men may control the fate of the Middle East!”). In 2018, its time has finally come.